West Indies Cricket Fans Forum

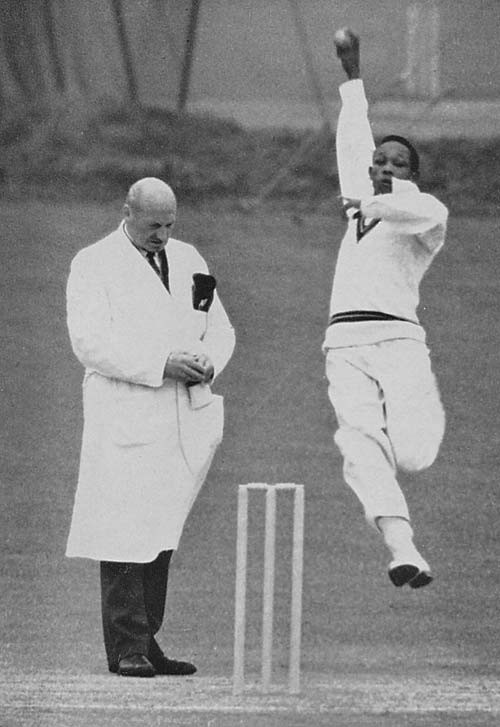

Roy Gilchrist: A fast-bowling terror!Roy didn’t fit the prototype physique of fast bowlers!

At the 2003 World Cup in South Africa, Shoaib Akhtar bowled the fastest recorded ball in the history of cricket. The sixth and final ball of his second over was bowled at Nick Knight, and was recorded at 161.3km/h or 100.2mph. This remains the fastest ball ever recorded, and would seem to give Shoaib some claim as the fastest bowler of all time. However, speed testing of fast bowlers is a very recent development, and many other players over history would also be able to make a reasonable case to be considered amongst the fastest bowlers of all time. Any list of fast bowlers will undoubtedly be extensive, and open to intense debate. Names such as Charles Kortright and Tibby Cotter who were both pre WWI, Jack Gregory, Harold Larwood and Learie Constantine who played between the wars, and then the multitude of quickies since then including Frank Tyson, Wes Hall, Charlie Griffith, Jeff Thompson and Michael Holding are often brought up. One of the more interesting characters included in this elite pace company is a relatively unknown West Indian called Roy Gilchrist, a player whose test career was over by age 24 and his place in cricket history clouded by both on and off-field indiscretions.

Roy was born on the 28th of June 1934 in Seaforth, Saint Thomas in Jamaica. He was the child of farm labourers, and grew up on a sugar plantation. The Great Depression had cast its cloud across much of the world, and had caused sugar prices to slump. Roy’s early childhood in Jamaica was characterised by widespread social discontent as the result of significant unemployment, pitiful wages, high prices, and appalling living conditions. It is clear that Roy undoubtedly grew into adulthood with a limited education and significant hardship. Michael Manley, a trade union leader and Jamaican Prime Minister, described Roy as being “burdened by those tensions which so often run like scars across the landscape of the personalities of people who come from poverty.” These factors undoubtedly were highly influential in Roy’s psychological journey into adulthood. Even as he started to make a name for himself as an exceptionally fast bowler, rumours of conflict with other players and team-mates started to surface.

Roy didn’t fit the prototype physique of fast bowlers, being quite short at about five foot eight inches tall and not being incredibly strong. He did, however, possess unusually long arms and his action made good use of this asset. Roy ran into the wicket at high speed, before unwinding with a high arm action. Roy’s natural pace and bounce saw him selected as a teenager to play for Serge Island in the sugar estates competition. His bowling was very erratic and wild, however, his obvious potential was clear to both opposing batsmen and the selectors.

Roy was soon picked for the Wembley Club that played in the Jamaican domestic cricket competition, the Senior Cup. His progress through the ranks then slowed, and it took him three more seasons before the selectors were prepared to pick him for the full-strength Jamaican team. Cricket in the West Indies in the 1950s was rife with racism and bias. The membership of most clubs were predominantly upper class whites, and players like Roy struggled for recognition. The captain the teams were always white, and any empathy or understanding of Roy’s situation in life was unlikely. Nonetheless, his performances were such that the Island selectors were compelled to choose Roy to make his first class debut at the age of 22.

Roy was first picked to represent Jamaica in a match at Bourda in Georgetown against the British Guiana in the Quadrangular Tournament on 11th, 12th, 13th, 15th and 16th of October 1956. His captain, Alfred Binns, gave him the new ball as British Guiana had first use of the wicket. On what would undoubtedly appear to be a flat wicket, British Guiana declared their first innings closed at 5 for 601, with four batsmen passing their century. Roy took a quite creditable 3 for 129 off nearly 40 overs. He was supported by his teammate, the great Alf Valentine, who bowled a mammoth 90.5 overs of his left arm orthodox in finishing with figures of 2 for 165. Jamaica replied with 469, and the match ended in a tame draw.

Roy’s next three matches for Jamaica were in March of 1957 against a touring Duke of Norfolk’s XI. In the first game at Sabina Park, Roy took his first five wicket bag for Jamaica, with 5 for 110 off 29.2 overs. He followed this with 1 for 53 in the Duke’s XI’s second innings. The next two matches against the Duke’s XI resulted in Roy returning the less than impressive figures of 2 for 63 and 1 for 64 in the second game, and 1 for 83 and 1 for 87 in the third. However, Roy must have shown considerable promise in this series of three matches, as he was picked to represent the West Indies on their 1957 tour of England.

Roy was still very young and inexperienced, and selection on the tour of England was clearly unexpected. At that point of West Indian history, the captain was still always a white man, in this case John Goddard. Roy was not familiar with protocol and the expectations of players representing their country, and there were again rumours of inappropriate behaviour by Roy on this tour. Roy played in three lead-up games against Northhamptonshire, Essex and the M.C.C., however, in spite of only taking one wicket in five innings, Roy was selected to make his Test debut against England in the First Test at Edgbaston on the 30th and 31st May, and the 1st, 3rd and 4th of June 1957.

Unlike previous eras, and certainly later ones, the West Indies bowling attack of 1957 was built around the joint spin attack of Ramadhin and Valentine. Roy was the sole pace bowler chosen for the Test matches, receiving medium paced support from the all-rounders Frank Worrell, Denis Atkinson and Gary Sobers. English captain Peter May won the toss in the First Test and chose to bat first. Frank Worrell bowled the first over, with Roy sharing the new ball. Roy took 2 for 74, however, the star for the West Indies was Ramadhin with 7 for 49 in England’s total of just 186. The West Indies made 474 in reply, with Roy being run out for a duck in his first test innings. England then posted a massive 4 for 583, with Peter May finishing on 285 not out. Roy bowled reasonably well in all the carnage, taking 1 for 67 off 26 overs. Atkinson, with 72 overs, and Ramadhin, with 98 overs, carried most of the load. The match ended in a draw, but not before the West Indies collapsed. Stumps on day five saw the West Indies struggling to avoid defeat at 7 for 72.

The four Test series was won by England two to nil, with victories in the Second Test at Lords by an innings and 36 runs and the Fourth Test at Headingly by an innings and 5 runs. The Third Test at Trent Bridge was drawn. Gilchrist produced some very quicks spells at times, however, his inaccuracy cost him. He took 4-115 at Lords, but 0 for 118 and 1 for 21 at Trent Bridge and 2 for 71 at Headingley. By the end of the tour, Roy had played more games for the West Indies than he had for Jamaica. Roy had shown some of his best form in the other tour matches, with a fine double of 5 for 41 and 2 for 27 against Derbyshire, and also 5 for 33 against Somerset.

The West Indies team returned home, with their next international series against the touring Pakistan side in 1958. Roy did not play another first class game after leaving England in September 1957 until the First Test against Pakistan, which started on the 17th of January 1958. While he had only taken ten wickets against England, Roy’s performances were sufficiently impressive to make him an automatic choice for the First Test. After the West Indies had scored an impressive 579, Roy bowled with impressive speed to take 4 for 32 in the rout of Pakistan for just 106. Another white man, Gerry Alexander, had taken over the captaincy of the West Indies, and he had little hesitation in enforcing the follow-on. Hanif Mohammad then produced one of the finest match saving innings of all time, scoring 337 in 970 minutes. Roy took 1 for 121, Pakistan totaled 657, and the match was drawn. The West Indies won the Second Test at Queen’s Park Oval in Port of Spain by 120 runs. Roy contributed strongly to the victory, taking 3 for 67 and 4 for 61. He made the early breakthrough for the home side in both innings, bowling the Pakistan opener Alimuddin twice for 9 and 0.

The Third Test at Sabina Park was also won by the West Indies, by an innings and 174 runs. Roy took 2 for 106 in Pakistan’s first innings total of 328. Pakistan probably would have been slightly disappointed that they didn’t get closer to 400, however, their disappointment quickly turned to absolute dismay as the West Indies piled on 3 declared for 790. This amazing total is largely remembered for Gary Sobers world record score of 365 not out, but few people now remember that Conrad Hunte was run out for 260 in the same innings, and was himself on track to break Len Hutton’s record score of 364. The game was effectively over when Alexander declared, and Roy took 1 for 65 in Pakistan’s second innings effort of just 288. The West Indies finished the series with another win at the Bourda Ground in Georgetown, being victorious by eight wickets. Roy took 4 for 102 and 2 for 66. The Fifth Test back at Queen’s Park Oval saw a major turnaround in form, with Pakistan winning by an innings and 1 run. Roy only bowled 7 overs in the game, and failed to take a wicket.

While Roy concluded the five Tests with 21 wickets at the fairly expensive average of 30.28, his pace had clearly unsettled many of the Pakistan batsmen, even on very dead pitches. His bowling was still erratic, and could be expensive, but there was no denying he had the sheer pace can defeat even the greatest players. Pakistan’s leading batsman, the great Hanif, admitted years later that the pace of Roy had scared him at times, saying “I live to this day the fear of a thunderbolt from Roy Gilchrist during that much celebrated visit to the West Indies in 1958.” Hanif recounted one particular delivery that just whistled past his nose, recalling “that delivery still sends shivers down my spine”.

The Fifth Test against Pakistan finished on the 31st of March, 1958, and Roy didn’t play another first class game for nearly eight months, when he was chosen for the back to back tours of India and Pakistan to being in November, 1958. Roy performed well in three leadup games to the First Test against India, but there were no real signs of what was to come. The West Indian selectors had paired Gilchrist up with another young fast bowler by the name of Wes Hall, and in this series, the two of them would become possibly the fastest bowling combinations of all-time.

The First Test at the Brabourne Stadium, Bombay on the 28th, 29th, and 30th of November, and the 2nd and 3rd of December 1958 finished in a draw. Gilchrist took 4 for 39 and 2 for 75, but his performances in this First Test are now better remembered for the emergence of a new delivery. The pitches in India were very low and slow, and Roy found them unproductive to bouncers. Roy decided, in his own manner, that the natural way to counteract this lack of bounce was not to have the ball bounce at all. The occasional ‘beamer’ happens to all bowlers, and generally is accidental. Roy’s beamers were neither occasional nor accidental. His comment was “I have searched the rule books, and there is not a word in any of them that says a fellow cannot bowl a fast full-toss at a batsman. A batsman has a bat and they should get the treatment they deserve”. India managed to draw the First Test, in spite of the beamers by Roy, largely due to a fine defensive innings of 90 by Pankaj Roy in 444 minutes.

The West Indian captain Gerry Alexander was evidently horrified by Roy’s deliberate beamers. Roy was ordered to stop bowling them, as Alexander considered them too dangerous to the batsmen’s health. Conflict between the bowler and captain, which had been simmering over the past year, started to come to a head after the game. Roy swore at Alexander, and Alexander demanded an immediate apology. Roy refused to do so, and Alexander told Roy that his tour was over and that he was to return to the West Indies. A delegation of the younger players, including Wes Hall, approached Alexander and requested that Roy be forgiven for his misdemeanor. Alexander agreed to this, however, Roy was warned that any future infractions would result in his immediate sacking. Roy was dropped from the Second Test in response to this episode, however, the reason given officially was that he had pulled a hamstring.

The West Indies won the Second Test, in spite of Roy’s absence, with Wes Hall taking eleven wickets in the match. Roy returned to the West Indies team for a match against Indian Universities, and promptly destroyed the students. He took 6 for 16 in the Universities total of just 49, and then hardly bowled in the second innings as the West Indies cruised to an innings victory. It was hard to leave him out of the team after a performance like that, and Roy returned to the West Indian team to share the new ball with Hall in the Third Test.

The Third Test at Eden Gardens in Calcutta saw the West Indies win by the small margin of an innings and 336 runs. After batting first and making 5 declared for 614, the West Indies bowled out India for 124 and 154. Roy took 3 for 18 and 6 for 55, and with Hall also taking three wickets in each innings, it was becoming clear that many of the Indian players had no wish to face either of the West Indian quick bowlers.

The Indian team had almost collapsed into chaos by the time of the Fourth Test. The captain in the previous three tests, Ghulam Ahmed, retired from all forms of cricket two days after the side had been announced. Polly Umrigar, who had been playing test cricket for a decade, was asked to take over to lead his country. Unfortunately, he had a fight with the selectors over the makeup of the team on the morning of the match, and he also quit. The great all-rounder, Vinoo Mankad, who is now better remembered for running out Bill Brown, was then chosen as captain. Roy continued to terrorise the Indian batsmen, and the West Indies won by 295 runs. He took 2 for 44 and 3 for 36, and his bowling was notable both for its pace and liberal use of bouncers and still, but less frequently, beamers.

The tension that had arisen between Alexander and Roy after the First Test had never really diminished. Clearly the divide between the Cambridge educated Alexander and Roy, who had come from poverty, was too significant. Whether it ever could have been overcome is difficult to know. The West Indies were going through substantial social reforms, and the previously defined class roles were rapidly disappearing. Roy’s complex personality needed sensitive and careful handling by his captain, and Alexander was not capable, or not willing, to do this. Regardless of his treatment by the captain, Roy was not especially popular with many of his teammates either. He was known to be a fiery and hostile bowler, but more than that, he was considered to have a malicious streak, and this was evidenced by his bowling of repeated beamers at the Indian batsmen.

The Fifth and final Test was held on a placid pitch at the Feroz Shah Kotla Ground at Delhi. The match ended in a draw, with no bowlers able to make any real impact. Roy took 3 for 90 and 3 for 63, but was outshone by the allround performance of Collie Smith, who scored a century and took 3 for 94 and 5 for 90 with his gentle offspinners. Roy finished the series with 26 wickets at 16.11 in four tests. The speed of Roy’s bowling can be best demonstrated by direct comparison with Wes Hall. Hall is largely regarded as one of the fastest bowlers of all time, however, the only Indian batsman to make a century in the series, Chandau Borde, rated Gilchrist as the faster of the pair. Gary Sobers also considered Roy Gilchrist to be the fastest bowler that he ever played with or against.

After the conclusion of the Fifth Test, the West Indies were to play one final tour match in India before departing for Pakistan. This match, irrelevant in the larger scheme of things, was to prove decisive in Roy’s international career. This last game was played at the Gandhi Sports Complex Ground in Amritsar against Northern Zone. On an under-prepared pitch, the West Indies were sent into bat, and were quickly dismissed for just 76. North Zone’s reply was even worse, making 59. Roy took 4 for 33 and Lance Gibbs 5 for 22. The West Indies faired a little better in the second innings, putting together a total of 228. The captain of North Zone, Swaranjit Singh, was a former colleague of Alexander at Cambridge, and he had evidently told Alexander that he would show the other Indian players how to deal with Roy. This news had filtered back to Roy, although who by is unknown. It was also said that Roy had a grudge against Singh following an article Singh had written about him. Clearly, fireworks were expected. Singh had been bowled by the first ball he faced in the first innings, but had made a solid start the second time around, being unbeaten on 15 just before lunch on the final day.

Roy bowled the final over before lunch, and after bowling a bouncer, tried to york Singh. Roy slightly underpitched the delivery, and Singh drove it back down the ground for four. Perhaps overconfident, or merely slightly silly, Singh said to Roy “You like that one? Beautiful wasn’t it?” The next ball, not unexpectedly for anyone who knew Roy, was a beamer straight at Singh’s head. Roy described it later as one of the fastest balls he ever bowled, and Singh was lucky not to wear it. Considerably unnerved by this, Singh edged the next ball but was dropped by Alexander. Roy followed this up with another beamer that Singh just managed to avoid. Alexander went to Roy at this point, and ordered him to stop bowling beamers. This message went unheeded, a third beamer for the over was sent down, and the two teams left the field for the lunch break.

Alexander approached Roy, and told him that he had bowled his last ball on the tour. Alexander then approached Singh, and asked him if he would have any objections to Roy being replaced. Not surprisingly, Singh was more than happy for this to occur, and Roy never walked back onto the field for the West Indies again. The tour selectors met at the end of play, and it was unanimously agreed that Roy would be sent home on the next available flight, while the rest of the team flew to Pakistan. Alexander informed Roy of this decision, which evidently was not well received. Quite what happened at the meeting remains a mystery, however, rumours of what transpired included everything from shouting through to Roy pulling a knife on Alexander.

Realising that his chances of playing again for West Indies were slim while Alexander was captain, Roy signed a contract to play professionally in England for Accrington in the Lancashire Leagues. He moved permanently to England, playing for a variety of different sides including Baccup, Middleton, Great Chell, Lowerhouse, Crompton and East Bierly over the following decades. Not surprisingly for a player of his talent, Roy dominated the Leagues, as his pace and bounce were simply beyond the capacity of most amateurs. He took an amazing 280 wickets in 1958 and 1959 for Middleton, and averaged over 100 wickets a season for nearly two decades.

Roy only ever played a handful more first class games, with a match at the Bourda Ground against Barbados in October 1961 his first at home since the Indian tour, and also his last game ever in the West Indies. On the basis of his form in England, Frank Worrell evidently requested him to be included for the 1960/61, however, the selectors refused point blank to consider it. Perhaps most interestingly, almost all of Roy’s first class cricket then took place in India. The BCCI, in an amazingly far-sighted manner, recognized that India would not become a Test power until they learn to play genuinely quick bowling. A group of fast bowlers including Roy, Chester Watson, Charlie Stayers and Lester King, spent a large part of the 1962/63 season playing for various Indian first class teams. Roy’s final first class match was for the Andhra Chief Minister's XI against the Indian Starlets in Hyderabad in March 1963. Roy took 0 for 83 and 1 for 38 in a drawn match.

Roy’s life off the cricket ground was, sadly, almost as tumultuous as that on the ground. He had married his girlfriend, Novlyn, and they had seven children together. Their marriage was a fiery one by all accounts. A very sad episode on the 2nd of June 1967 saw Roy attack Novlyn after a dispute over him attending a party. Roy had grabbed her by the throat, held her against a wall and then branded her with a nearby hot iron. Roy was, appropriately, charged with this assault, and was given three months probation. The judge commented at the sentencing that “I hate to think that English sport has sunk so far that brutes will be tolerated because they are good at games.” There were no further reported incidents of abuse, but Roy’s volatile nature meant that the marriage was undoubtedly not a quiet and peaceful affair.

Roy lived in England for twenty six years before eventually returning home to Jamaica in 1985. He had Parkinson’s Disease, which would eventually be the cause of his death at the early age of 67. Roy died at home on the 18th July 2001 at Portmore, St Catherine, Jamaica. Roy’s career is one of promise ultimately unfilled, and the question of whether a more empathetic captain such as Frank Worrell could have guided Roy to greatness will remain unknown.

Career Statistics

Test Matches

From 1957 to 1959, Roy played in 13 test matches. He took fifty seven wickets at an average of 26.68. His best bowling figures were 6 for 55. Roy also scored 60 runs at an average of 5.45, with a highest score of 12. He took 4 catches in his test career.

First Class Games

In his 42 first class games, Roy took 167 wickets at an average of 26.00, with a best bowling of 6 for 16. He also scored 258 runs at an average of 7.81, with a highest score of 43 not out. He also took 10 catches.

Guyana Diaspora Forum

We have a large database of Guyanese worldwide. Most of our readers are in the USA, Canada, and the UK. Our Blog and Newsletter would not only carry articles and videos on Guyana, but also other articles on a wide range of subjects that may be of interest to our readers in over 200 countries, many of them non-Guyanese We hope that you like our selections.

It is estimated that over one million Guyanese, when counting their dependents, live outside of Guyana. This exceeds the population of Guyana, which is now about 750,000. Many left early in the 50’s and 60’s while others went with the next wave in the 70’s and 80’s. The latest wave left over the last 20 years. This outflow of Guyanese, therefore, covers some three generations. This outflow still continues today, where over 80 % of U.G. graduates now leave after graduating. We hope this changes, and soon.

Guyanese, like most others, try to keep their culture and pass it on to their children and grandchildren. The problem has been that many Guyanese have not looked back, or if they did it was only fleetingly. This means that the younger generations and those who left at an early age know very little about Guyana since many have not visited the country. Also, if they do get information about Guyana, it is usually negative and thus the cycle of non-interest is cultivated.

This Guyana Diaspora Online Forum , along with its monthly newsletter, aims at bringing Guyanese together to support positive news, increase travel and tourism in Guyana and, in general, foster the birth of a new Guyana, which has already begun notwithstanding the negative news that grabs the headlines. As the editor and manager of the publication, I am committed to delivering Blog entries and Newsletters that are politically balanced, and focused on the positive ideas we wish to share and foster among Guyanese.

| ||||